|

T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE INCREDIBLE STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

AGE OF CRUSADE

Wikipedia

The Crusades were military campaigns sanctioned by the Latin Roman Catholic Church during the High Middle Ages and Late Middle Ages. In 1095 Pope Urban II proclaimed the First Crusade with the stated goal of restoring Christian access to holy places in and near Jerusalem. Many historians and some of those involved at the time, like Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, give equal precedence to other papal-sanctioned military campaigns undertaken for a variety of religious, economic, and political reasons, such as the Albigensian Crusade, the Aragonese Crusade, the Reconquista, and the Northern Crusades. Following the First Crusade (1095-1099 and immediate aftermath) there was an intermittent 200-year struggle for control of the Holy Land, with six more major crusades and numerous minor ones. In 1291, the conflict ended in failure with the fall of the last Christian stronghold in the Holy Land at Acre, after which Roman Catholic Europe mounted no further coherent response in the east.

THE MUSLIM INVASION AND THE RECONQUISTA

FROM BBC

INTRODUCTION

Islamic Spain (711-1492)

Islamic Spain was a multi-cultural mix of Muslims, Christians and Jews. It brought a degree of civilisation to Europe that matched the heights of the Roman Empire and the Italian Renaissance.

Islamic Spain was a multi-cultural mix of the people of three great monotheistic religions: Muslims, Christians, and Jews.

Although Christians and Jews lived under restrictions, for much of the time the three groups managed to get along together, and to some extent, to benefit from the presence of each other. It brought a degree of civilisation to Europe that matched the heights of the Roman Empire and the Italian Renaissance.

Outline

In 711 Muslim forces invaded and in seven years conquered the Iberian peninsula.

- It became one of the great Muslim civilisations; reaching its summit with the Umayyad caliphate of Cordovain the tenth century.

- Muslim rule declined after that and ended in 1492 when Granada was conquered.

- The heartland of Muslim rule was Southern Spain or Andulusia.

Periods

Muslim Spain was not a single period, but a succession of different rules.

- The Dependent Emirate (711-756)

- The Independent Emirate (756-929)

- The Caliphate (929-1031)

- The Almoravid Era (1031-1130)

- Decline (1130-1492)

The Alhambra Palace, the finest surviving palace of Muslim Spain, is the beginning of a historical journey in this audio feature, In the Footsteps of Muhammad: Granada.

CONQUEST

The Conquest

The traditional story is that in the year 711, an oppressed Christian chief, Julian, went to Musa ibn Nusair, the governor of North Africa, with a plea for help against the tyrannical Visigoth ruler of Spain, Roderick.

Musa responded by sending the young general Tariq bin Ziyad with an army of 7000 troops. The name Gibraltar is derived from Jabal At-Tariq which is Arabic for 'Rock of Tariq' named after the place where the Muslim army landed.

The story of the appeal for help is not universally accepted. There is no doubt that Tariq invaded Spain, but the reason for it may have more to do with the Muslim drive to enlarge their territory.

The Muslim army defeated the Visigoth army easily, and Roderick was killed in battle.

After the first victory, the Muslims conquered most of Spain and Portugal with little difficulty, and in fact with little opposition. By 720 Spain was largely under Muslim (or Moorish, as it was called) control.

Reasons

One reason for the rapid Muslim success was the generous surrender terms that they offered the people, which contrasted with the harsh conditions imposed by the previous Visigoth rulers.

The ruling Islamic forces were made up of different nationalities, and many of the forces were converts with uncertain motivation, so the establishment of a coherent Muslim state was not easy.

Andalusia

The heartland of Muslim rule was Southern Spain or Andulusia. The name Andalusia comes from the term Al-Andalus used by the Arabs, derived from the Vandals who had been settled in the region.

Stability

Stability in Muslim Spain came with the establishment of the Andalusian Umayyad dynasty, which lasted from 756 to 1031.

The credit goes to Amir Abd al-Rahman, who founded the Emirate of Cordoba, and was able to get the various different Muslim groups who had conquered Spain to pull together in ruling it.

The Golden Age

The Muslim period in Spain is often described as a 'golden age' of learning where libraries, colleges, public baths were established and literature, poetry and architecture flourished. Both Muslims and non-Muslims made major contributions to this flowering of culture.

A Golden Age of Religious Tolerance?

Islamic Spain is sometimes described as a 'golden age' of religious and ethnic tolerance and interfaith harmony between Muslims, Christians and Jews.

Some historians believe this idea of a golden age is false and might lead modern readers to believe, wrongly, that Muslim Spain was tolerant by the standards of 21st century Britain.

The true position is more complicated. The distinguished historian Bernard Lewis wrote that the status of non-Muslims in Islamic Spain was a sort of second-class citizenship but he went on to say:

Second-class citizenship, though second class, is a kind of citizenship. It involves some rights, though not all, and is surely better than no rights at all...

...A recognized status, albeit one of inferiority to the dominant group, which is established by law, recognized by tradition, and confirmed by popular assent, is not to be despised.

Bernard Lewis, The Jews of Islam, 1984

LIFE FOR NON-MUSLIMS IN ISLAMIC SPAIN

Jews and Christians did retain some freedom under Muslim rule, providing they obeyed certain rules. Although these rules would now be considered completely unacceptable, they were not much of a burden by the standards of the time, and in many ways the non-Muslims of Islamic Spain (at least before 1050) were treated better than conquered peoples might have expected during that period of history.

- they were not forced to live in ghettoes or other special locations

- they were not slaves

- they were not prevented from following their faith

- they were not forced to convert or die under Muslim rule

- they were not banned from any particular ways of earning a living; they often took on jobs shunned by Muslims;

- these included unpleasant work such as tanning and butchery

- but also pleasant jobs such as banking and dealing in gold and silver

- they could work in the civil service of the Islamic rulers

- Jews and Christians were able to contribute to society and culture

The alternative view to the Golden Age of Tolerance is that Jews and Christians were severely restricted in Muslim Spain, by being forced to live in a state of 'dhimmitude'. (A dhimmi is a non-Muslim living in an Islamic state who is not a slave, but does not have the same rights as a Muslim living in the same state.)

In Islamic Spain, Jews and Christians were tolerated if they:

- acknowledged Islamic superiority

- accepted Islamic power

- paid a tax called Jizya to the Muslim rulers and sometimes paid higher rates of other taxes

- avoided blasphemy

- did not try to convert Muslims

- complied with the rules laid down by the authorities. These included:

- restrictions on clothing and the need to wear a special badge

- restrictions on building synagogues and churches

- not allowed to carry weapons

- could not receive an inheritance from a Muslim

- could not bequeath anything to a Muslim

- could not own a Muslim slave

- a dhimmi man could not marry a Muslim woman (but the reverse was acceptable)

- a dhimmi could not give evidence in an Islamic court

- dhimmis would get lower compensation than Muslims for the same injury

At times there were restrictions on practicing one's faith too obviously. Bell-ringing or chanting too loudly were frowned on and public processions were restricted.

Many Christians in Spain assimilated parts of the Muslim culture. Some learned Arabic, some adopted the same clothes as their rulers (some Christian women even started wearing the veil); some took Arabic names. Christians who did this were known as Mozarabs.

The Muslim rulers didn't give their non-Muslim subjects equal status; as Bat Ye'or has stated, the non-Muslims came definitely at the bottom of society.

Society was sharply divided along ethnic and religious lines, with the Arab tribes at the top of the hierarchy, followed by the Berbers who were never recognized as equals, despite their Islamization; lower in the scale came the mullawadun converts and, at the very bottom, the dhimmi Christians and Jews.

BAT YE'OR, ISLAM AND DHIMMITUDE,

The Muslims did not explicitly hate or persecute the non-Muslims. As Bernard Lewis in The Jews of Islam, 1984 puts it:

in contrast to Christian anti-Semitism, the Muslim attitude toward non-Muslims is one not of hate or fear or envy but simply of contempt

An example of this contempt is found in this 12th century ruling:

A Muslim must not massage a Jew or a Christian nor throw away his refuse nor clean his latrines. The Jew and the Christian are better fitted for such trades, since they are the trades of those who are vile.

WHY WERE NON-MUSLIMS TOLERATED IN ISLAMIC SPAIN?

There were several reasons why the Muslim rulers tolerated rival faiths:

- Judaism and Christianity were monotheistic faiths, so arguably their members were worshipping the same God

- despite having some wayward beliefs and practices, such as the failure to accept the significance of Muhammad and the Qur'an

- The Christians outnumbered the Muslims

- so mass conversion or mass execution was not practical

- outlawing or controlling the beliefs of so many people would have been massively expensive

- Bringing non-Muslims into government provided the rulers with administrators

- who were loyal (because not attached to any of the various Muslim groups)

- who could be easily disciplined or removed if the need arose. (One Emir went so far as to have a Christian as the head of his bodyguard.)

- Passages in the Qur'an said that Christians and Jews should be tolerated if they obeyed certain rules

OPRESSION IN LATER ISLAMIC SPAIN

Not all the Muslim rulers of Spain were tolerant. Almanzor looted churches and imposed strict restrictions.

The position of non-Muslims in Spain deteriorated substantially from the middle of the 11th century as the rulers became more strict and Islam came under greater pressure from outside.

Christians were not allowed taller houses than Muslims, could not employ Muslim servants, and had to give way to Muslims on the street.

Christians could not display any sign of their faith outside, not even carrying a Bible. There were persecutions and executions.

One notorious event was a pogrom in Granada in 1066, and this was followed by further violence and discrimination as the Islamic empire itself came under pressure.

As the Islamic empire declined, and more territory was taken back by Christian rulers, Muslims in Christian areas found themselves facing similar restrictions to those they had formerly imposed on others.

But, on the whole, the lot of minority faith groups was to become worse after Islam was replaced in Spain by Christianity.

There were also cultural alliances, particularly in the architecture - the 12 lions in the court of Alhambra are heralds of Christian influences.

The mosque at Cordoba, now converted to a cathedral is still, somewhat ironically, known as La Mezquita or literally, the mosque.

The mosque was begun at the end of the 8th century by the Ummayyad prince Abd al Rahman ibn Muawiyah.

Under the reign of Abd al Rahman III (r. 912-961) Spanish Islam reached its greatest power as, every May, campaigns were launched towards the Christian frontier, this was also the cultural peak of Islamic civilisation in Spain.

In the 10th century, Cordoba, the capital of Umayyad Spain, was unrivalled in both East and the West for its wealth and civilisation. One author wrote about Cordoba:

There were half a million inhabitants, living in 113,000 houses. There were 700 mosques and 300 public baths spread throughout the city and its twenty-one suburbs. The streets were paved and lit...There were bookshops and more than seventy libraries.

Muslim scholars served as a major link in bringing Greek philosophy, of which the Muslims had previously been the main custodians, to Western Europe.

There were interchanges and alliances between Muslim and Christian rulers such as the legendary Spanish warrior El-Cid, who fought both against and alongside Muslims.

Muslim, Jewish and Christian interaction

How did Muslims, Jews and Christians interact in practice? Was this period of apparent tolerance underpinned by a respect for each other's sacred texts? What led to the eventual collapse of Cordoba and Islamic Spain? And are we guilty of over-romanticising this period as a golden age of co-existence?

Three contributors discuss these questions with Melvyn Bragg. They are: Tim Winter, a convert to Islam and lecturer in Islamic Studies at the Faculty of Divinity at Cambridge University; Martin Palmer, an Anglican lay preacher and theologian and author of The Sacred History of Britain; and Mehri Niknam, Executive Director of the Maimonides Foundation, a joint Jewish-Muslim Interfaith Foundation in London.

The collapse of Islamic rule in Spain was due not only to increasing aggression on the part of Christian states, but to divisions among the Muslim rulers. The rot came from both the centre and the extremities.

Early in the eleventh century, the single Islamic Caliphate had shattered into a score of small kingdoms, ripe for picking-off. The first big Islamic centre to fall to Christianity was Toledo in 1085.

The Muslims replied with forces from Africa which under the general Yusuf bin Tashfin defeated the Christians resoundingly in 1086, and by 1102 had recaptured most of Andalusia. The general was able to reunite much of Muslim Spain.

REVIVAL

It didn't last. Yusuf died in 1106, and, as one historian puts it, the "rulers of Muslim states began cutting each other's throats again".

Internal rebellions in 1144 and 1145 further shattered Islamic unity, and despite intermittent military successes, Islam's domination of Spain was ended for good.

The Muslims finally lost all power in Spain in 1492. By 1502 the Christian rulers issued an order requiring all Muslims to convert to Christianity, and when this didn't work, they imposed brutal restrictions on the remaining Spanish Muslims.

RECONQUISTA 717-1492 CHRISTIAN KINGDOMS OF SPAIN — VERSUS MOSLEM MOORS

from Heritage History (go to site for details of biographies, battles etc.)

INTRODUCTION :

The Moorish Empire was firmly established on the Hispanic Peninsula in 711 after the Battle of Guadalete. The conquering Mohammedan armies vanquished the Visigoth kingdom in a stroke, and quickly over-ran much of the Iberian Peninsula. Their expansion was not permanently checked until they contended with the Frankish kingdom north of the Pyrenees, twenty years hence. By that time, the Moors controlled all of the Iberian Peninsula outside of the mountainous Christian Kingdom of Asturia in the Northwest. The subsequent wars fought between Christian and Moslem powers on the Iberian Peninsula, over the next 750 years are often collectively referred to as the Reconquista, because the general trend over time was for the Christian kingdoms that originated in Asturia to gain territory from the Moslem Moors. But it took the Christians nearly 8 centuries to regain the region they had lost in one blow, and very few significant gains in territory were made until the 11th century.

The Wars of the Reconquista are relatively difficult to follow for those unfamiliar with Spanish history. They occurred intermittantly and were complicated by civil wars within both the Christian and Moslem kingdoms, so many of the battles were regional conflicts rather than part of a united Christian or Moslem front. There were Moslems subjects living in Christian domains and Christian subjects living in Moslem domains; treachery and politicking abounded, and independent Christian princes sometimes allied themselves with Moors against their Christian enemies, and visa versa. The battles considered here are primarily those between Christian and Moorish powers. Civil wars within the Christian and Moorish kingdoms that occurred contemporaneously are dealt with elsewhere.

The region under Moorish control on the Iberian Peninsula was referred to as Andalusia, and within a few years of the Moslem conquest it included all of Spain except the Northwesternmost corner. In 756 a new Emirate was formed, independent of the Caliph of Baghdad and Cordova was maintained as the Moorish capital. This city became a center for Moorish civilization and commerce, and for much of the ninth and tenth centuries, it was one of the most prosperous and cultured cities in Europe. It remained the Moslem capital until the early 11th century when Caliphate of Cordova collapsed entirely and the Moorish empire broke up into independent kingdoms. Soon afterward two empires arose and fell in Moslem North Africa (the Almoravids, and the Almohads), and their leaders attempted to gain control of the Moorish kingdoms in Iberia. These Berber princes held court in Seville for much of the 12th and 13th centuries, but never consolidated all of the Moslem kingdoms under their control. They spent much of their time fighting with Christian kingdoms to the north, and also with rival Moslem kingdoms. During these centuries the Christians made great gains against the divided Moors, and when Seville finally fell in 1248, the moslem kingdom of Granada, which had already been established as a vassal state of Castile became the last remaining Moslem stronghold. Granada continued to thrive for over two centuries before the last of the Moorish kingdoms was driven from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492 by Isabella and Ferdinand.

EARLY CONFLICTS : 717 TO 778

When the Moslems over-ran Spain in the early 8th century, a band of Christians, led by a Visigoth prince, took refuge in the mountain fastnesses of Northern Spain. In about 717, the Moors made an attempt to drive them out, but were soundly defeated, and chose to allow them to remain unmolested. This historic battle at the Cave of Covadonga, is probably more properly considered as part of the Moorish Conquest of Spain that of the Reconquista—except for the fact that it was a Christian victory, and assured the survival of a sovereign Christian realm within Hispania. It is therefore often considered the first battle of the Reconquista even though almost all serious contention between the Christian kingdoms of Spain and the Moorish powers was delayed for at least 200 years.

It was the Frankish kingdom in Gaul, rather than the isolated and overwhelmed Christians of northern Spain, that opposed the Moorish expansion over the Pyrenees. Even after their decisive victory over the Moors at Tours in 732, the Franks continued to fight the Mohammedans, particularly over the coastal region of Catalonia. In 778 however, the Franks, under the command of the great Christian warrior Charlemagne, withdrew all of their forces from Spain due to conflicts in Saxony. During their retreat over the pass of Roncevalles the rear guard was attacked, and this formed the basis of the legend of the "Death of Roland". With the retreat of the Franks, the king of Asturia was officially recognized by the Pope as a sovererign Christian kingdom within Spain. From this beginning, the kingdoms of Leon and Castile, which were to eventually reconquer all of Spain and Portugal for Christiandom, eventually emerged.

The Moorish kingdom of Cordova was founded in 756 by Abderrahman I, a prince of the Umayyad family who had fled from the Abbasids in Syria. A civil war between the two families was raging in the Moslem world, and he was welcomed in Spain, where the Umayyad dynasty still held sway. There he worked to establish a centralized government independent of the Abbasid family, which had assumed the Caliphate in the middle east. He was successful as a military leader as well as an administrator, and Cordova became an important commerical and cultural center. There were few major conflicts between Moors and Christians during the 8th and 9th centuries. During much of this time the prestige and power of Cordova was at its height, and the Kingdom of Asturia was able to defend its borders, but could not serious contend with the Mos the early tenth century however, the power of Cordova was beginning to wane, and the Kingdom of Asturia was becoming more powerful. Over a thirty year period, between 910 and 940, Asturia split into the two kingdoms of Leon and Castile, and in 939 Ramiro II of Leon succesfully stood against Abderrahman III at the battle of Alhandega (a.k.a Simancas). The caliphs that followed Abderrahman III were not of a high calibur, and infighting among the Moors continued until the rise of Almansur, a leading Moorish general, in 977. For the next 25 years Almansur reigned supreme, regained all Moslem territory lost to the Christians, and sacked many important cities. He fought other Moslem princes as well as Christians and succeeded again in bringing all of Moorish Spain under his dominion. We have few details of most of his battles but he is said to have fought in 57 campaigns was was victorious in almost all. Finally the Christian kingdoms united against him, and at the Battle of Calatanazor, he was defeated and killed.

The death of Almansur changed the aspect of things considerably. The royal family from whom he had usurped power was effectively dispossessed of the throne, and Almansur left no worthy heir. After his death his empire began to disintegrate, and thirty years later (1031), the Caliphate of Cordova collapsed entirely. With the Moorish leadership in dispute, the Christian kingdoms of Leon and Castile sought to regain the territory they had lost to Almansur, and when it was opportune, made alliances with Berber moslems to defeat the Moorish princes. Castilians fought alongside the Berbers when they sacked Cordova in 1010. And during the following century, the Christian kingdoms began to make their first real headway against the disunited Moorish kingdoms on their borders.

WARS OF THE ALMORAVIDS : 1031 TO 1130

Almanzor, the Moorish general Hispania to its greatest extent, made use of Berber armies from Africa in his wars against Leon and Castile. After his death in the early eleventh century, these Berber mercenaries did much to keep the Moors in a state of disarray, to the benefit of the Christian kingdoms. With the fall of Cordova in 1011, and the complete collapse of the Caliphate in 1031, the Moorish empire split into a dozen independent, and often warring, kingdoms. These independent fiefdoms were far more vulnerable to Christian encroachment than a united Moorish empire, and they suffered as much from internal divisions and civil war as they did from the Christians.

The early elevenths century, saw much civil war in both Moslem and Christian realms, and complicated skirmishes between various Berber, Christian and Moorish factions, but eventually, under Ferdinand I (the Great), the combined kingdoms of Castile and Leon began to rise to a dominant position among the Christian states, and expand its borders at the expense of both its Moorish and Christian neighbors. Alfonso VI was the son of Ferdinand, and after fighting his brothers to gain control of all of his father's dominions, he began to make serious incursions into Moorish territory.

Back in North Africa during this time, a new Berber dynasty, the Almoravids, had taken over Morocco and was increasing their sphere of influence. In 1085 Alfonso VI succeeded in capturing Toledo and its surrounding areas, and at that point, the Moslem princes of the Iberian Peninsula called upon the Almoravids to help them defend themselves against their Christian enemies. Another Berber army then arrived en force, led by the great Almoravid conqueror Yusuf, and dealt the Christians a serious blow at the battle of Zalaka (a.k.a Sagrajas). It was only a temporary set back however. The Christians recovered and spent much of the next century battling the Moors with considerable success.

The great hero of this era was El Cid, a loyal knight who first served Ferdinand I, and later his sons Sancho and Alfonso VI. Although many of his legendary feats have no reliable historical corroboration, he was undoubtedly the greatest military hero of his age, and an exemplar of all of the best traits of medieval chivalry. It is known with certainty that during the lifetime of El Cid, the Christian Kingdoms captured much Moorish territory, including the great Moorish strongholds of Toledo and Valencia.

Even after the death of Cid the the Moors continued to lose ground to the Christians. The Almoravids in Iberia never succeeded in uniting all of the Moslem princes under their sway, and in 1147, the Almoravids of Africa fell to the Almohad dynasty just as the disunited Moors in the far west surrendered Lisbon to Afonso I, the conquering Christian King of Portugal.

WARS OF THE ALMOHADS, AND COLLAPSE OF MOORISH SPAIN : 1147 TO 1350

Then in 1147, the Almoravids of Africa fell to the Almohads, another war-like Berber dynasty whose early years were marked by extensive conquests and buchery. The Almohads sought to establish a presence on the Iberian peninsula and became involved in several civil wars between Moorish princes. They ended up taking Seville (1148), and Granada(1155), and in 1170 moved their capital to Seville. The Moorish empire remained divided however, and the Christians continued to attack Moorish territory. In 1195, the Castilians raided the province of Seville, and the Almohad Caliph of Morrocco crossed the sea with a large army, and dealt the Castilians a terrible blow at Alarcos.

For a time the tide turned in favor of the Almohads, but the next Almohad Caliph began to persecute infidels and conquer Christian cities, and so alarmed all of Christian Europe. In 1211, when the Almohads raised an enormous army of over 100,000 Berbers and Moors, Alfonso VIII of Castile led a united army of Spaniards and European Christians against them. The largest and most decisive battle of the Spanish Reconquista was fought July 16, 1212 near the plain of Las Nava de Tolosa in southern Spain. Alfonso VIII surprised the Mohammedans and caught them off guard. The entire Moslem army was slain and the power of the Almohads was nearly crushed in one blow. During the following forty years the Christian kingdoms of Castile, Portugal, and Aragon, under the leadership of (Saint) Ferdinand III all made significant gains at the expense of the Moors. They permanently captured the cities of Badojoz(1228), Majorca(1229), Jaen (1232), Cordova(1236), Valencia (1238), and Seville(1248), and gained almost all of the Iberian Peninsula, save Granada, a region on the southern coast.

The Moorish exiles who left the conquered cities fled south towards Granada. The ruler of Granada at the time was Mohammed ibn Nar and instead of fighting the Christians he sought to make an alliance with them. He agreed to become a vassal state and help the Castilians in their wars, including the overthrow of Moorish Seville. By proving his loyalty by taking arms against the his Moslem brethren, he won a reprieve from the King of Castile who thought it useful to have a Moslem "buffer" state in his realm. Mohammed founded the Nasrid dynasty, which lasted over 250 years and during his lifetime maintained peaceful relations with Ferdinand III, the victorious monarch of Castile.

WARS OF GRANADA : 1300 TO 1492

Granada had become a vassel state of the kingdom of Castile in 1236, and relations between the two kingdoms remained relatively stable while Mohammed Alhamar, the founder the kingdom of Granada, lived. After the deaths of Ferdinand III of Castile and Mohammed Alhamar however, both Castile and Granada suffered from palace intrigue and infighting. Conditions did not break out into serious warfare, however, until 1319 when a Castilian army attacked Granada, but was soundly defeated by the Moorish general.

The following years saw continued hostilities between Granada and Castile and after the defeat of Mohamed IV at the battle of Teba, he made an alliance with the emir of Morocco. The Moroccans took Gibralter and helped Granada in its wars against Castile, and in 1340 an enormous army from Africa crossed the straight. This was the first real threat to the Christian kingdoms' domination of Hispania, and resulted in a great battle at Rio Salado, in which the united Christians prevailed over the Moslem invaders.

For the following century, Granada and Castile settled in to a series of truces, occasionally interrupted by assassinations, or skirmishes, but both kingdoms suffered more from civil wars and internal dissention than from conflict between them. The second half of the fourteenth century saw Europe ravaged by the black death, and appallingly corrupt rulers, including the Infamous Pedro the Cruel, on the throne of most of the kingdoms of Spain. Granada therefore had over a century of reprieve while the Christians fought largely among themselves.

In 1474 Isabella and Ferdinand came to the throne, combining the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. They spent the first years of their reign putting down divisions within their empire and with other Christian kingdoms, but by 1482 were prepared to undertake a concerted war against Granada, and to drive the last Moorish kingdom off the Iberian Peninsula. Granada was wracked at this time by internal divisions between Muley Abdul Hussan and Boabdil, and Spain was greatly strengthened by both the courageous military leadership of Ferdinand, and the astute statesmenship of Isabel. The army of Spain also included several of the most renowned soldiers of the age including Gonsalvo de Cordova, Hernan Perez del Pulgar and Ridgrigo Ponce de Leon.

The Castilian War against Granada lasted for over ten years years, and was carried on by a series of systematic attacks on fortifications, and seiges of cities. Granada is the Moorish word for Pomegranate, and Ferdinand famously said he would ‘pluck the pomegranate, seed by seed’. The fighting between Christian and Moslem was furious when it occurred, but most of the war was marked by long seiges, and chivalric skirmishes between the two armies. The important port city of Malaga fell in 1487 and with it, the last chance for help from Africa. The ongoing conflict between the two rival claiments to the throne of Granada greatly impaired the kingdom's ability unite in resistance to Ferdinand. Granada, the capital city was finally besieged in 1491 and a year later, Boabdil, the last Moorish king, surrendered the city to the Spaniards.

The Moors who continued to live in the region under Spanish rule were called Moriscoes and pockets of resistance continued for several years after the fall of Granada. For a time many of the Moriscoes lived peaceably, but under worsening oppressions. Isabella and Ferdinand sought to drive non-Christians from their realm and in 1492 expelled all Jews from their dominions. The final expulsion of the Moriscoes was delayed until 1610, after a severe and bloody uprising. But the loss of both the Jews and Moriscoes, who were largely of the urban, craftsman, and merchant classes, was a great blow to Spain economically, especially over the long term.

SPAIN

THE MUSLIM INVASION AND THE RECONQUISTA

SUMMARY

----------------------------------------------------

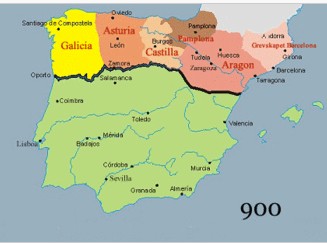

In 711 when the Muslims invaded from North Africa Spain Christian and split into independent states. They conquering most of the country before being stopped. The ‘re-conquering’ (‘reconquista’) by the Christians was the effort by the Christians to recover this territory. Its progress is shown in the maps below. By 1300 only Granada was unconquered but not retaken until 1492. This period saw almost incessant warfare. Mercenaries changed sides depending on who paid the most. Muslims fought each other, sometimes united with Christians. The story of Muslims remaining in Spain after 1492 can be found under Moriscos.

Four stages are recognised.

Wars of Cordova : From 790 -900 (100 years)

Wars of the Almoravids : From 900 - 1150 (250 ywars)

Wars of the Almohads, and Collapse of Moorish Spain : From 1150 - 1300 (150 years)

Wars of Granada : 1300 to 1492 (200 years)

(Note: Historians differ in how this overall period is divided)

Spanish Reconquista 790 -1300

The Reconquista

James K Powell II

(13.26)

The Golden Age of Spanish Jewry

(Essential Lectures in Jewish History)

Dr. Henry Abramson (11.09))

|

CLICK BUTTON TO GO TO SECTION |

|

Wars of the Almohads, and Collapse of Moorish Spain : 1147 to 1350 |