|

T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

See our new site:

SUMMARY

_____________________

SAHAR HASSAMAIN SYNAGOGUE

Wikipedia

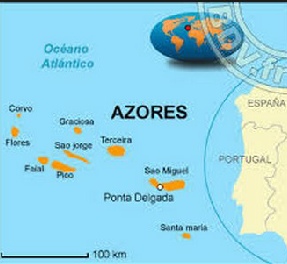

The Synagogue Sahar Hassamain ( "Gate of the Heavens") is located at 16 Rua de Brum, Ponta Delgada, on São Miguel Island in the Azores. It is the oldest synagogue in Portugal built after the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian peninsula.

The Synagogue Sahar Hassamain ( "Gate of the Heavens") is located at 16 Rua de Brum, Ponta Delgada, on São Miguel Island in the Azores. It is the oldest synagogue in Portugal built after the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian peninsula.

HISTORY

The Sahar Hassmain synagogue is one of only a few remnants of Jewish culture in the Azores and in all Portugal. Founded by Abraham Bensaúde along with other members of the Jewish community of the city in 1836, in a building purchased for this effect. It is the oldest synagogue in Portugal built after the expulsion of the Jews from the country. There were formerly five synagogues in Ponta Delgada, and Sahar Hassmain is the only one still existing.

The first references to the establishment of Jewish families in the Azores is from the first half of the nineteenth century. Jews came to the Azores from Morocco because of the economic restrictions that were being imposed on them there at the time. In the same period, the influence of the Catholic Church had declined in Portugal, and the advent of liberalism, particularly after the Liberal Revolution of Porto (1820), attracted Jews to the Azores. Jews were accepted at the time, in contrast to the persecution by the Inquisition in previous centuries. It is likely that those Jews that arrived had Portuguese ancestry. Family names from this period are Abohbot, Benarus, Levy, Zagory and Besabat.

TODAY

Sahar Hassmain synagogue was closed for more than fifty years. As of March 2009 it is temporarily open on Saturdays for guided tours in the context of the celebrations of 420 years of the arrival of the first Jews to the Azores. Services are no longer conducted. The municipality undertook recently to support the recovery process of the synagogue although the property is owned by the Jewish Community of Lisbon. The synagogue is located on an upper floor of a building that also included the rabbi’s residence. The exterior of the building is not recognizable, since it was built with the façade of a typical Azorean dwelling house. The interior retains its original character and on display are some objects of worship, especially a chair of circumcision from 1819, chandeliers and diverse historical documentation in Hebrew. The archipelago came to have other synagogues on the islands of Terceira and Faial. Besides this synagogue, there remains only the Jewish cemetery of Santa Clara also in Ponta Delgada, from 1834, and the Cemetery in Angra do Heroismo from 1832.

In 2010 were found cult objects, manuscripts and printed documents which constitute a valuable collection of the history of the community. The site of the former synagogue were donated by the Jewish Community of Lisbon and the Municipality of Ponta Delgada, which is finalizing the technical projects for the recovery of the property, seeking its reclassification as a museum and promoting it for cultural and tourism. In April 2015 it was announced that restoration was completed.

Lecture by Prof. Fátima Sequeira Dias of University of the Azores - see LINKS Below

In 2004, a genetics study concluded that 13.4% of the Y chromosome of Azoreans is of Jewish origin, a fact that suggests the importance of the Jewish presence in the Azores over many centuries. There are three major instances of the Jewish presence in the Azores - the first dates back to the original settlement of the Azores in the 15th century; the second takes place in the first quarter of the 19th century and the third coincides with the period of the Nazi nightmare in Europe. Commerce was the main economic activity of the Azorean Jewish community, but the islands became too small for their business objectives. The only family to remain on the islands was the Bensaúdes, who have undertaken the most successful investments in the Azores to this day.

HISTORY

International Survey of Jewish Monuments

The heritage of Jewish history, culture, and life on the Azores is grim and sad. Among the Jewish communities of the world that have vanished, that of the Portuguese-owned Azores in the Atlantic Ocean was not well known even while it flourished. Two of the islands, Terceira and Sao Miguel, each had a Jewish community for at least 200 years. Members of these communities came from Portugal, Morocco and perhaps also Spain and Gibraltar. They engaged mostly in commerce and shipping.

The first documented Jewish settlement began in 1818; by 1848 the numbers rose to 250; the most important of the communities was in Ponta Delgada. But some contend that Jews came to the islands already in the late 15th century; "The Jewish presence in the Azores had two moments," said the director of the municipal department of culture and history on the island of Terceira, Francisco dos Reis Maduro Dias, quoted in the The Forward (January 9, 1998). "The second, which began at the start of the 19th century and continued through the 20th century, is well documented. The first, which coincided with the discovery and the settlement of the Azores in the 15th and 16th centuries, is not documented at all. All we know is that Jews were here and, like those on the mainland, were pressured to convert."

During World War II, the Azores became a haven for some Ashkenazi Jews from Germany and Poland who managed to flee Europe by way of the Iberian Peninsula. After the war the Ashkenazi dispersed, while the native Sephardi population dwindled through emigration and death and intermarriage. Salom Delmar, who took care of the synagogue and cemetery until he passed away in 1990, and now his son, Jorge Delmar, sustains the memory of the community as best he can. "Thirty years ago, there were 16 Jewish families on this island," Delmar told Myrna Katz Frommer in 1998. "We were a community. We had services in the old synagogue and made all the festivities in my grandfather's house. But all the others have died or converted or moved away. I am the only one left."

[Encyclopaedia Judaica, v.3, p.1013; Charlotte Weisbrot, “Time seems to stand still in Azores synagogue”. Canadian Jewish News, 10/2/1986; Myrna Katz Frommer, Letter from the Azores, Forward, January 9, 1998; and Dias, Fatima, 1999 "The Jewish community in the Azores from 1820 to the present in From Iberia to Diaspora: Studies in Sephardic History and Culture, Ed. Yedida K.Stillman e Norman A. Stillman, Brill, Leiden, Boston, Koln.]

JEWISH AZORES

By Judith Fein, San Diego Jewish Journal

There were several puzzling things about the Jewish cemetery on the island of Terceira in the Azores — a lush, volcanic, Portuguese archipelago in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. First, a plaque on the outside wall called the cemetery a “field of equality” and profusely thanked “the most illustrious members of the city council” for selling the Jews the land.

“Jews believe that everyone’s equal in death — rich, poor, old, young,” my guide said to my husband Paul and me.

Hmm, I thought. I’ve never seen writing about equality at a Jewish cemetery. And why the profuse thanking for being allowed to purchase land? The words indicated to me that the Jews were trying to ensure their safety, proclaim their loyalty or curry favor in some way. I wasn’t sure how.

Second, the tombs bore no Jewish symbols. Most of them were horizontal slabs of stone, shaped like the outlines of human bodies, but there were no lions, menorahs, hands outstretched in a priestly blessing. Instead, each one had a simple, stylized motif of a flower, and all the flowers looked alike.

I reflected on the history of the Jews in Portugal. When the Spanish Inquisition forced Jews to convert or leave, many fled to Portugal. Because of their wealth and skills, King Joao II offered permanent or temporary residency to a large number of them. When Joao II died and Manuel became king, he wanted to consolidate his power by marrying into the family of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain; they agreed on the condition that Manuel expel all the Jews from Portugal. In 1496, after some of them had left, Manuel forcibly converted the remaining ones to Christianity. Even after baptism, they had to go to great lengths to profess their Catholic faith. There were secret Jews who, in public, adopted Christian customs while they continued their clandestine religion at home. There were Jews who sincerely converted and became Catholics. But, officially, there were no longer any Jews left in Portugal.

For about l5 years, I’ve gone on the trail of these Jews. They fled to the hills of Portugal and to destinations like Holland, the Ottoman Empire, Brazil, North Africa and the U.S. They often escaped to remote places, and I thought about that constantly in the Portuguese Azores. There were hints and some elusive facts, but I couldn’t pin anything down about a crypto-Jewish presence. All I knew was that starting in 1818, some Jews from North Africa whose ancestors had fled started showing up in the Azores, which was duty free, and where they could import and resell merchandise to local businesses. The Inquisition ended in 1821, and Jews were “tolerated” in Portugal. A group of them came to Terceira, and I was staring at about 50 of their tombs, which bore names like Abohbot, Benarus, Levy, Zagory and Bensabat.

By chance, I was introduced to Francisco dos Reis Maduro Dias, an archeologist, historian and museum curator with knowledge about the history of the Azorean Jews. I was afraid he’d laugh at me, but he took my questions seriously. He had some thoughts about why the word “equality” appeared on the plaque.

In 1820, a liberal revolution in Portugal received widespread support on Terceira. The liberals espoused the idealistic trilogy of the French revolution: liberty, fraternity and equality. They also tolerated religious diversity, although there were no outward religious signs. Was this why there were no Jewish symbols on the tombs?

Then Maduro Dias told me about Mimon Abohbot. He had led the fledgling Jewish community in Terceira, because there was no rabbi and he was knowledgeable and respected, and he wanted to assure Jewish continuity. He had a Moroccan Torah; his home was the de facto synagogue; and he wrote five books by hand, meticulously, lovingly, which contained all the prayers a Jewish family would need for all occasions. One of them was in the museum in Terceira.

I hate to beg, but at that moment I felt that the most urgent thing in the world was to see the hand-written prayer book and the Torah. “Please, please, can I see it?” I asked Maduro Dias.

He smiled. Was that a yes?

It was. A few days later, at the museum where he curates in the city of Angra do Heroismo, he led me into a classical library, crammed with books, and a long wooden table where he invited me to sit. He handed me a pair of white gloves and gently placed Mimon Abohbot’s gilt-edged, handwritten prayer book in my hands. The owner’s name was on the cover, which also bore a floral motif. At the back of the book was what looked like a genealogy. As I carefully turned the pages, my eyes lingered on a Hebrew phrase that means, “I was, I am, I will be.” The Eternal presence of the Divine. Sitting in the library, holding the book, I felt as though I had entered a sacred space.

“How can I see the Torah and have someone tell me about it?” I asked Maduro Dias.

“Let me see what I can do,” he said. “It’s in the pubic library in Ponta Delgada on Sao Miguel island.”

Before I left, I asked him why there was there a coastal village named Porto Judeu — the Jewish port. He said one possible explanation came from l6th century chronicles. Apparently, the first settlers who came to Terceira were afraid when they reached the shore. They said to a Jewish man with them, “Jump, Jew!” and this was the harbor where he jumped.

I jumped on a plane, flew 25 minutes to Sao Miguel and hurried to the public library. We followed a librarian named Margarida Oliveira into a room where the Rabo de Peixe Torah had been lovingly placed in a horizontal glass case. The parchment looked weathered, and had burn marks on it.

“There is a very mysterious story around this Torah,” Oliveira began. “It was found in a cave in 1997 by two kids. Unfortunately, they vandalized it, giving away and selling parts of it. They showed a piece to their religious teacher, who contacted the library. After analysis and restoration in Lisbon and Israel, the Torah was dated to the early l8th century in Morocco, probably the Torah of Maimon Abohbot.”

But why did the 300-year-old Sephardic Torah have a modern, machine-stitched, blue and gold, Ashkenazi-style mantle? A Portuguese Jew in Israel named Inacio Steinhardt, who’s done important research about the Azorean Jews, believed that Abohbot purchased the Morrocan Torah in London and brought it and another Torah to Terceira, where he used it in his home synagogue. His will stipulated that the Torah would remain in Angra as long as his descendants were there. But if they left, and no Jews remained, one of the Torahs would go back to Morocco and the other would go to the main synagogue —Shaar Hashamaim — in Ponta Delgada. There is no record of what happened to the Torahs.

Steinhardt discovered that there was a Jewish captain on the American military base on Terceira named Marvin Feldman who had obtained a Torah locally in 1970. After six years of searching, Steinhardt finally located him in Australia. Feldman said that on the base he led Shabbat services and was known as “the American Jew.” Some locals confided to him that they had Jewish origins, and they piqued his curiosity about the Jewish presence in the Azores. His search led him to Porto Judeu where, in a bar, some of the older men told him their version of the town’s name. In the l6th century, fugitive Jews were caught in a storm and sought refuge on land on Terceira. The governor of Terceira let them live on the island, but not in the man city of Agra. They settled in Porto Judeu.

One day, the locals handed Feldman a wooden box. Afraid to open it because it might have contained human remains, he looked inside: there was the 18th century Torah, which he took to the base. A Catholic priest knew Hebrew and read from it during services. As for the mantle, he’d had it made in the U.S.

In l973, Feldman departed the base and left the Torah behind. In 1997, it was found in the cave by the two kids. How did it get to Ponta Delgada? Who stashed it in a cave? And why? Was it stolen? Sequestered? Why did it have burn marks? Hmmm, I thought. There are echoes of the Dead Sea Scrolls here.

As I turned to leave the library, Margarida whispered to me, “I think my ancestors were Jewish.”

I thought this was the last important stop on the Jewish detective tour, but boy was I wrong. The tourism department informed me that a man wanted to meet me at the old synagogue. I had already walked by it before; it looked like a nondescript row house, with no writing, signs or Jewish symbols, and it was locked.

When I arrived, accompanied by two women from the tourism department, Jose de Almeida Mello — a bespectacled man with close-cropped dark hair — stood in front of the door. He greeted me in hesitant English and introduced his friend Nuno Bettencourt Raposo, a lawyer, who spoke English well. The former put a key in the lock and opened the creaky door of what he said had been a rabbi’s home; it was also used as a synagogue called “Sahar Hassamain.” He explained that he was a historian, and that both he and Bettencourt Raposo were Catholic. He said the people who built this synagogue in 1836 came from Morocco. “What we have here is very important — it is the oldest synagogue in Portugal since the Inquisition,” he exulted.

Inside, the abandoned house/synagogue was in a sorry state. We walked from an entry room to the room that housed the mikvah, or ritual bath, and saw the hole where rainwater flowed in, and the remnants of a drain and tile work.

Almeida Mello said he sees the synagogue as a symbol of religious tolerance. In 2008 he published a book about it and told the large crowd at the launch that it was “an SOS for the synagogue. We must do something now to preserve it, or it will be too late.” The city officials placed him in charge of promoting the synagogue and raising money.

“I descend from those New Christians,” Almeida Mello confided. “My ancestor was Manuel Dias, a trader. Actually, I believe that 99 percent of Portuguese people have Jewish blood because the Jews have been in Portugal for 2,000 years.”

He had a book in his hands, and he showed me that all his life when he held any book, he turned it over, and then opened it right to left — the way Hebrew is read, right to left.

“The Jewish religion never interested me,” Almeida Mello said, “but I’m fascinated by the culture. I am a religious Catholic man, but this synagogue is my passion.”

I was intrigued by his story, but underwhelmed by the building itself…until he invited us to follow him upstairs, cautioning us to use the right side of the wooden staircase, as the middle was unstable.

Upstairs were the rabbi’s living quarters. Light streamed in from outside.

“Now for the surprise,” Almeida Mello said. “Up until today, it has been a secret.” In the dining room, he opened what looked like a pantry door. “Come,” he said. I gasped aloud at what I encountered on the other side: an entire synagogue, with 30-foot-high light blue walls, a bimah, 65 carved wooden seats around the outside of the sanctuary, a chandelier and a circumcision chair. Strewn around were old prayer books, which had probably been unseen and untouched for more than 60 years.

“The synagogue was constructed inside the rabbi’s home because religious buildings had to be behind walls, with no visible identification on the outside. Inside here, it was away from the eyes of the townspeople.”

He said he had found a box in the synagogue and didn’t touch it for seven years.

“There were dead mice inside. Then, one night, in 2009, I started thinking about it. I bought gloves and a mask at a pharmacy, then opened the box and threw everything on the ground. I was totally shocked—there were manuscripts, books, parchment, fabrics, mezuzahs, phylacteries.” Almeida Mello looked at me with great intensity. “Now you understand why this is so important!”

In a hushed voice, I said that in all my travels, I had never seen anything like this. I had beheld hidden arks and sequestered shelves that held objects of worship, but an entire synagogue?

I followed him to the balcony where women once sat and prayed, sequestered behind an iron grillwork railing. I could hear their whispered talk, feel the presence of those souls who were now gone. I picked up a prayer books and held it close to my heart for a moment.

“I can still feel the presence of the Jews here,” I said, to no one in particular. “Yes,” said one of the women from the tourism board. “It is here. In us. I think we are all descended from them.”

IF YOU GO:

For more information about the Azores: www.VisitPortugal.com and www.visitazores.com/en

For four-hours flights from Boston and between the islands: SATA airlines: www.SATA.pt

For more about the synagogue: www.sinagogapontadelgada.com

About the author and photographer:

Judith Fein is a multiple-award-winning travel writer who has contributed to more than 100 publications and is the author of “Life is a Trip: The Transformative Magic of Travel.” Paul Ross is an award-winning photojournalist. Their Web site is www.GlobalAdventure.us.

REDEDICATION OF SYNAGOGUE MARKS MILESTONE FOR AZOREAN JEWISH HERITAGE

By Michael Holtzman Herald News Staff Reporter, Apr 29, 2015

PONTA DELGADA, Azores — The expulsion of Jews from Portugal at the outset of the Inquisition in 1496 gained a significant and symbolic reversal with the rededication Thursday of the oldest synagogue in this country.

People of multiple cultures and religions celebrated the restoration and reopening of the synagogue, called Sahar Hassamain (Gates of Heaven), in memorable fashion.

Abandoned for at least 50 years after prosperity faltered and Jews slowly left the island, the synagogue, hidden inside a rabbi’s simple urban home, fell into disrepair until the call went out and the work of many — from average citizens to coordinated governments — began to restore and save it from ruin.

“This effort highlights the important Jewish legacy that exists in the Azores in this synagogue, now transformed into a cultural center and museum for our city,” Ponta Delgada Mayor José Manuel Bolieiro said in Portuguese at the rededication inside the restored, intimate sanctuary of carved rich woods, a tabernacle holding holy Torahs of Jewish scripture held for safe-keeping in Lisbon and other original artifacts that stood a test of time.

About 100 people — with more than a dozen media personalities, the bishop, ambassadors to Portugal from America and Israel, military, business and cultural leaders — listened from the sanctuary. Others sat in the small balcony once reserved for women in the Orthodox temple. And nearly 200 people sat just outside, watching and listening on four TV monitors.

Workers had readied the inauguration ceremony by hoisting the gold, red and gray banners of Ponta Delgada. Two women dusted and cleaned the inner sanctuary, and police security details began blocking access from Rua do Brum, where the synagogue is located a couple of blocks from City Hall.

Bolieiro proudly said his city on the island of São Miguel — which once had five synagogues — “can now be included among the world’s cities with a Jewish legacy” and will attract visitors.

“Putting Ponta Delgada on the map of Jewish heritage cities is the next step, which is sure to impact our tourism,” Bolieiro said.

About 80 people, many with ties to the Azorean or Jewish communities in Greater Fall River and New England, traveled to Ponta Delgada earlier in the week to participate in the historic events.

“Portugal would not be what it is today without the rich Jewish culture, customs and experiences interwoven in its history. The story of the Jews of Portugal is long and powerful, and it is a story that begs to be told,” said Fall River-area state Sen. Michael Rodrigues, one of several speakers in the sanctuary.

That story includes returning families with names like Bensaude, Delmar and Abecassis in the early 19th to early 20th century, bringing commercial and trade prosperity to Portugal and the islands, as well as important cultural growth.

A STORY THAT IS ABOUT TO END THE JEWS OF THE AZORES

MerLuxuryTravel, Myrna Katz Frommer and Harvey Frommer

“I am the last Jew in all of the Azores,” says Jorge Delmar. He is a stocky man in his early fifties who runs an import/export business in Ponta Delgada, the capital city of Sao Miguel, largest of the nine islands that comprise the Portuguese archipelago. “Thirty years ago, there were sixteen Jewish families on this island,” he adds. “We were a community. We had services in the old synagogue and made all the festivities in my grandfather’s house. But all the others have died or converted or moved away. I am the only one left.

“My wife and children are Catholic. We have no problems over religion, although my wife is curious. She’ll ask, ‘Why do you say you are a Jew? What happened to the Jews?’ I say, ‘As my mother is a Jew, I am always a Jew. That’s all.’”

Delmar’s connection to the Azores had its beginning in 1818 when the Bensaude family of Morocco came to this volcanic archipelago, mythologized in lore as the remnants of the lost continent Atlantis, seeing opportunity in its developing orange-growing industry. They made their fortune trading agricultural products for manufactured goods with England and trading bills of exchange while transporting emigrants to Brazil. In the process, according to Fatima Sequeira Dias, Professor of Economic History at the University of the Azores, they changed the nature of the Azorean economy.

“The Bensaudes had the trade connections that enabled them to link England, Brazil, and Newfoundland with the Azores,” she says. “When they got into the bill of exchange business, that was the beginning of banking in the Azores.” This single Jewish family, she maintains, succeeded in integrating the islands’ economy, establishing a chain of retailers throughout the archipelago who offered imported goods on easy terms, and developing its maritime transport industry. Today a financial empire with international interests, the Bensaudes continue to be the Azores’ chief economic entity. But they are no longer Jewish. Fearful of a Nazis occupation of Portugal, most converted during the Second World War. Vasco Bensaude, the last Jew of the dynasty, died some twenty years ago.

Back in the nineteenth century, however, the example of this family coupled with growing prosperity in the Azores served as a beacon for North African Jews, among them Jorge Delmar’s great-grandfather who immigrated from Tangiers and found work in the Bensaude tobacco factory. Jewish communities emerged throughout the islands. At one time, there were five synagogues on Sao Miguel alone, several more on the islands of Terceira and Faial.

Only one remains: Sahak Hassamain, consecrated in 1893 in a sixteenth century building on a busy downtown street in Ponta Delgada. Through the mid 1960s, it held services continuously; afterwards the premises were maintained by two Jewish sisters who lived in the building. But since their death, it has fallen into disrepair. Only Jorge Delmar stands between the synagogue’s existence and extinction. “I pay the taxes and for the electricity and water. I keep the Torah, six silver candelabras, and the other heirlooms in my home. Maybe one day the synagogue will be rebuilt and they can be put back in their rightful place,” he says. “It seems impossible, but I have a hope.”

Delmar escorts us up the rickety staircase and through an arched wooden door. We enter the high-ceilinged sanctuary with its bimah of beautiful old wood, its ark draped with a green curtain on which the Ten Commandments are embroidered in gold. He points to the second row where as a child he would sit beside his uncle. His grandfather sat next to the reader’s desk. “We never had a rabbi. The oldest Jew was in charge, and that for many years was my grandfather.”

We go up a second unstable stairway to the women’s balcony whose walls are decorated with plaques attesting to the synagogue’s founders; three are members of the Bensaude family: Abraham, Solomon, and Elias. But everywhere there is disorder and disrepair as furnishings, prayer books, phylacteries and tallit succumb to the island’s humidity.

From a window in the women’s section, we can see a restored building across the way whose cornerstone reads 1719. It seems every building in this downtown section of Ponta Delgada has been restored. Walls are whitewashed and attractively trimmed with gray basalt, the Azores’ ubiquitous volcanic rock. Pretty gardens are dotted with little orange trees and enclosed by neat stone walls; narrow cobblestone lanes are swept clean. Only in this aging house of worship, it would seem, is there such desolation.

It is a ten minute ride from the synagogue to Ponta Delgada’s unmarked Jewish cemetery, a small field behind a basalt wall on a non-descript suburban street. A number of the Bensaudes are buried here as are all of the Delmars. There is one last place reserved for Jorge. He regularly recites Kaddish for his uncle, mother and grandfather at the appointed times, but he knows there will be no one to say Kaddish for him.

A second Jewish cemetery exists on the island of Faial. It is famous for its 1958 volcanic eruption and the marina in its capital city Horta which draws clippers and yachts from all over the world. But few know about the little burial ground on the bottom of a hill overlooking the sea. A Catholic cemetery takes up the greater part of the hillside; its orderly tombstones are heaped with flowers, there for the picking on an island where uncultivated calla lilies, hydrangeas, and white irises line the roads and fill the fields. At a certain point, the cemetery gives way to a flower-dotted expanse that ends at a low wall. On the other side are seventeen Jewish graves.

No flowers grace these tombstones, but names and dates of the deceased can be easily read. The most recent grave is that of Moses Benarus who died in 1942. His son, Joseph, was the last Jew in Faial before he converted to Catholicism shortly before his death, and Joseph’s daughter Luna remains the final link to a Jewish presence on this island. A practicing Catholic, the affable middle aged woman feels some need to hold on to a heritage she but dimly remembers from her childhood. “My father used to talk to me about his family’s history all the time,” she says. “He would tell me about his grandfather, Joseph, who came to the Azores in 1860 and his father, Moses, who became a diplomat and hosted visiting dignitaries from the United States. In March 1907, his guest was President Theodore Roosevelt.

“Moses was a practicing Jew,” Luna adds. “He would go to the synagogue in Lisbon and observed all the Jewish customs. My father identified himself as a Jew, but he had no Jewish life because by the time he was grown, there were no other Jews on the island. I think that is why he finally converted. But before he died, he arranged for someone to take care of the Jewish cemetery where his father, his infant brother, and his grandfather are buried.”

Together with her husband, Luna operates Quinta Das Buganvilias, a luxurious seaside inn on the renovated property of her mother’s family’s farmstead. But she also maintains the townhouse in Horta that belonged to her father and grandfather, and it is here that she stores the treasured mementos of a Jewish past. In the old oak bookcase are siddurs, worn copies of the Old Testament, a book of Psalms, a Haggadah. And on a great carved desk is a framed photograph of Luna as a little girl draped with a golden ornament on which, in Hebrew, the word “Shalom” is inscribed.

It would appear that Jorge Delmar and Luna Benarus will close the book on the story of the Jews of the Azores. But some researchers believe there is another Jewish story on this archipelago in the middle of the Atlantic, one that pre-dates the Bensaudes’ arrival by some three hundred years, which continues to live on in mysterious ways.

“The Jewish presence in the Azores had two moments,” says Francisco dos Reis Maduro Dias, Director of the Department of Culture and History on the island Terceira.. “The second, which began at the start of the 19th century and continued through the 20th century, is well documented. The first, which coincided with the discovery and settlement of the Azores in the 15th-16th centuries, is not documented at all. All we know is that Jews were here and, like those on the mainland, were pressured to convert. But Portugal is different from Spain where they keep things separate. In Portugal, the people melded together. It is not as easy to find marks.

“Nevertheless, some attitudes, some habits of this earlier Jewish presence persisted that we are just now beginning to recognize. We believe today that perhaps there was some connection between the Jews of that time and the evolvement of the Cult of the Holy Spirit.”

Maduro Dias is referring to a uniquely Azorean ceremony/festival held at the fanciful little chapels, which look like a cross between a one-room schoolhouse and a wedding cake decoration, that one sees all over the islands. Each year, on the seven Sundays following Easter, roughly corresponding to the period between Passover and Shavout or the counting of the omer, these otherwise unused emporiums, as they are called, come to life. Re-painted, re-decorated and profusely adorned with flowers, they become the site of worship of the Holy Spirit, confirmation-type ceremonies for pre-pubescent children, and the fulfillment of pledges made earlier in the year, typically feasts to which the entire community and even strangers are invited. Sometimes a type of flat bread made without yeast and stamped with the seal of the crown of the Holy Spirit is used.

“No one will tell you the cult of the Holy Spirit is a Jewish custom,” Maduro Dias says. “It was born within Christianity during the 11th and 12th centuries through brotherhoods who contested the divinity of Christ. But we believe it was used and perhaps developed by the Jews at a certain moment as a means of coexisting with the larger culture.”

It is easy to see why New Christians, still Jewish in their hearts, would be attracted to the cult. “The entire procedure has nothing to do with the church,” according to Maduro Dias. “The emporiums have no crosses, no representations of holy figures. Those who hold their keys are not the same as those who hold the keys to the churches. Moreover, the Holy Spirit is God with no Christ. It is the presence of an abstract God.

“Therefore, these festivals allowed the Conversos an opportunity to be together in a separate moment, to keep some of their original attitudes within the frame of Christianity, to perform some acts meaningful to them and at the same time accepted as normal by the Christian community.”

Feasts and brotherhoods connected with the cult of the Holy Spirit were widespread in Medieval Europe and lingered in Portugal into the 19th century. But while the cult died out everywhere else, inexplicably it developed a powerful following in the Azores, and to this day continues to be a defining aspect of the islands’ culture, extending even to émigré communities in the United States. One group of Azorean-American still maintains its emporium on the island of Flores. Every year, a number of people return to Flores, perform the rituals and partake of the festival. Afterwards, they clean up, close the doors to their little temple, and return to America.

It is yet another irony of Jewish history that this totally Catholic institution once served as a sanctuary for Azorean Jews forced to convert, allowing them, at a time of the year that resonated with sacred overtones, to relate to their vision of God in an environment absent of Christian symbolism. But whatever Jewish yearnings and customs are embedded in this cult, whether its embrace by New Christians centuries ago had anything to do with the unique hold it has on Azorean culture is shrouded in the mist of undocumented history.

Today the only concrete evidence of a Jewish presence in the Azores belongs to its second community: a couple of cemeteries and a deteriorating synagogue which Jorge Delmar, for the past twenty years, has struggled to preserve.

“It is easy to be a Jew anyplace now,” says the last Jew in the Azores. “But here we are soon to be no more. This synagogue should remain as a reminder that once we were here. The government spend lots of money rebuilding churches, why not this synagogue? Many good things happened there. People who played an important part in the local history worshipped there.

“We did a study and found restoration would cost about $200,000. I keep trying to get it done. I write letters, I meet with government officials and potential donors. I don’t give up. We have a new government now so I am more hopeful.

“Why do I do this?” he asks. “Because I feel I have to do something. It all ends with me.”

About the Authors: Myrna Katz Frommer and Harvey Frommer are a wife and husband team who successfully bridge the worlds of popular culture and traditional scholarship. Co-authors of the critically acclaimed interactive oral histories It Happened in the Catskills, It Happened in Brooklyn, Growing Up Jewish in America, It Happened on Broadway, It Happened in Manhattan, It Happened in Miami. They teach what they practice as professors at Dartmouth College.

They are also travel writers who specialize in luxury properties and fine dining as well as cultural history and Jewish history and heritage in the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean. More about these authors.

You can contact the Frommers at:

AMERICAN TRAVELERS RETURN JEWISH LIFE TO SECRET PORTUGUESE SHUL

Malori Asman, owner of Amazing Journeys, which specializes in leading tours for Jewish singles, first heard about the Sahar Hassamain Synagogue from Cheryl Stern, a prospective client from the Boston area inquiring about the company’s June 5-17 tour of mainland Portugal and the Madeira and Azores islands.

Jewish Exponent, Philadelphia, Toby Tabachnick - July 13, 2016

A small synagogue, unused since the 1960s and hidden in a house on an unassuming street in Ponta Delgada — an island town in Portugal’s Azores islands — once again was filled with the sound of Shabbat prayers last month, thanks to 33 Jewish tourists led by a Pittsburgh-based travel company.

Malori Asman, owner of Amazing Journeys, which specializes in leading tours for Jewish singles, first heard about the Sahar Hassamain Synagogue from Cheryl Stern, a prospective client from the Boston area inquiring about the company’s June 5-17 tour of mainland Portugal and the Madeira and Azores islands. Stern asked Asman if she planned to take her group to visit the recently refurbished synagogue on the island of São Miguel while there.

Stern told Asman that she had a “special connection to the Azores” because her father, Aaron Mittleman, who died last February, had been instrumental in securing the funds for the renovation and preservation of the shul. It was a project he had worked on for almost 30 years.

Mittleman, a resident of Fall River, Mass., had been in Ponta Delgada on a business trip in 1987 along with several colleagues, including Paula Raposa, who had grown up in that town before immigrating to Massachusetts in the 1960s.

While having coffee in a cafe, the group was told of the hidden synagogue, which happened to be next door to Raposa, who is Catholic. She recalled that the group was able to obtain the key to the building that housed the 19th-century synagogue and take a look.

She was stunned.

“I was born there, and my parents were born there,” Raposa explained. “No one knew about that synagogue. It was a secret.”

The Sahar Hassamain (Gates of Heaven) Synagogue, once home to a small but thriving Jewish community, was in total disrepair, Raposa said, but she was touched by the beauty of the sanctuary, as well as its historical significance.

When she returned home to Massachusetts, she and Mittle-man established a nonprofit to raise funds to refurbish the synagogue and turn it into a museum to honor the Jewish presence that was once so important to the island. After years of work and navigating administrative red tape, Raposa and Mittleman were able to secure a grant from European Union groups devoted to the preservation of historical monuments in the amount of 300,000 euros.

“The Jewish people who built that synagogue had a huge impact on business there,” Raposa said. “We felt it was important to preserve an important piece of history.”

The refurbished 67-seat sanctuary was rededicated on April 24, 2015 with a Shabbat service of 40 people, about half of them Jews. It was the first known Jewish service in the Azores in nearly 50 years, The Herald News reported at the time.

While the building has received more than 6,000 visitors to tour its museum of Jewish artifacts since the rededication, and the sanctuary has four Torahs in its ark, it is not used for services because there are no practicing Jews left on the island, according to Raposa.

There are, however, many Crypto-Jews — those whose ancestors were forced to convert to Catholicism during the Spanish Inquisition — who maintain Jewish customs such as lighting candles on Friday nights, but often don’t know why.

When Asman heard about the synagogue from Stern, she put it on her group’s itinerary, and booked a tour of the museum. But after exploring the building, members of the group wanted to know if they could celebrate Shabbat there the next day.

At first, the administrator at Ponta Delgada’s city hall refused. But after much persistence, and the involvement of a state senator from Massachusetts and the town’s mayor’s office, the group got the green light to hold a service at Sahar Hassamain.

Asman picked up Portu-guese sweet bread at a local market, bought some wine and, along with the Shabbat candlesticks with which she typically travels, set up a Kabbalat Shabbat service for her group.

“It was so touching,” Asman said. “This is a building that was built for prayer, and it had been so long since Jews occupied the area. It was so meaningful to fill the room with prayer, as it was intended.”

For traveler Yvette Diamond of Owings Mills, Md., the service at Sahar Hassamain took on special significance because it came on the heels of a stop in Lisbon when the group heard of the tragic history of the Jews in Portugal who had fled Spain seeking refuge during the Inquisition. They were forced to convert or had their children taken and sold to become slaves to the Portuguese.

The shul is housed in what was the home of a rabbi, built in 1836 and was concealed from the public. The building contains a mikvah, and the bimah is in the center of the sanctuary in typical Sephardic fashion, Diamond said.

Heidie Rothschild of Alex-andria, Va., said it was an amazing experience.

“For me, I’m not very much a practicing Jew, but … it felt like a very nice way to return to Judaism.”

Toby Tabachnick writes for The Jewish Chronicle, an affiliated publication of the Jewish Exponent.

A Hidden Jewish “Archive” in the Azores

The Jewish Community in the Azores From 1820 to the Present,

Fatima S. Dias, Univeristy of the Azores

In 1818, North African Jews whose ancestors had been expelled from Spain came to the Azores. This was duty free and allowed them to import and resell to local businesses. In 1820, the Portuguese liberal revolution led to religious diversity.

Today, Portugal’s oldest post Inquisition synagogue the Shaar Hashomaylum Synagogue, which was built around 1820 and consecrated in 1836 is being restored. Work was completed in 2015.

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

The AZORES and the JEWS

NÚCLEO CULTURAL E MUSEOLÓGICO DE PONTA DELGADA

pdl.tv 2015 (1.22)

A Sinagoga " Sahar Hassamain" localiza-se na Rua do Brum nº 16, em Ponta Delgada. Recuperada e inaugurada pela Câmara em 2015, como Espaço Cultural e Museológico , destaca-se por ser uma das mais antigas de Portugal e um dos poucos vestígios da cultura hebraica nos Açores.

The Synagogue " Sahar Hassamain" is located at rua do Brum nº 16 in Ponta Delgada. It was restored and reopened by the municipality of Ponta Delgada in 2015 as a Cultural Centre and Museum. It's one of the oldest of its kind in Portugal and one of the few traces of the hebraic culture in the Azores.

Sahar Hassamain Synagogue Restoration

Michael Rodrigues 2015 (5.26)

SINAGOGUE- PONTA DELGADA

ReportTVs (1.59)

|

Rededication of synagogue marks milestone for Azorean Jewish heritage |

American Travelers Return Jewish Life to Secret |